This man saved my life – I live by his example

A little boy from an Italian village, a 'hopeless case', Alessandro Tamburrini's life was saved by an American surgeon. It's to that man, his friend and guide, that he dedicates his own surgical career. Interview by Seren Boyd

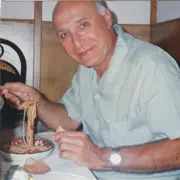

Among Alessandro Tamburrini’s most treasured possessions are a set of lab coats he will never wear and a photo of an American tackling a bowlful of spaghetti.

When he first met this man, Alessandro was three years old and not expected to live.

He had become acutely unwell in the spring of 1991 and been diagnosed with a rare and advanced pelvic rhabdomyosarcoma. His prognosis, according to his doctors in Rome, was terminal.

However, thanks to his family’s fierce determination and a pioneering medical team in New York, Alessandro pulled through.

The American in the picture is Professor Peter Altman, the paediatric surgeon who saved his life. The professor would become a lifelong friend and the inspiration for Alessandro’s career in medicine too.

Mr Tamburrini (pictured below) is now a consultant thoracic surgeon at University Hospital Southampton. More than 30 years later, he is still overwhelmed by the enormity of that gift – Prof Altman’s decision to take on his ‘hopeless’ case. And he is still trying to pay it forward.

‘I live thanks to him, and a number of other people but primarily him,’ says Mr Tamburrini, ‘and I try to do what he was doing.'

Despite 30 years of medical advances, the cure rate for Alessandro’s type of soft-tissue sarcoma remains low; the five-year survival rate is still less than 30 per cent.

Back in 1991, established diagnostic and treatment pathways did not exist and his doctors in Rome deemed his case hopeless. Yet, Alessandro’s family refused to accept that.

Alessandro’s great uncle, Eugene Cannata, owner of a big construction company in New York, approached Prof Altman, then director of paediatric surgery at Columbia University, and persuaded him to take on his nephew’s case.

‘My uncle is the type of person that can make the impossible possible,’ says Mr Tamburrini. ‘He is a true second father to me.’

His mother then defied doctors’ orders in Rome by discharging her son at night and flying him out to the US.

The paediatric multidisciplinary team at Columbia University under Prof Altman designed a ‘near-experimental’ chemotherapy and radiotherapy regime for Alessandro. Then, Prof Altman and urologist Professor Terry Hensle operated on 22 July 1991 to remove a sarcoma which was occupying the entire pelvis and lower abdomen.

I live thanks to him, and a number of other people but primarily him, and I try to do what he was doing

Alessandro Tamburrini

For decades to follow, Alessandro had many other admissions, complications and surgeries.

‘The amount of chemotherapy I had was enormous so there were consequences for my bones, my kidneys and several endocrine functions,’ says Mr Tamburrini. ‘From 1996 to 2002, I was having knee surgeries almost every year.

‘I still take medications to this day. But most people, probably everyone, would be surprised to hear what happened to me. It’s impossible to tell. Yes, I do have a lot of scars but I work, I do sports, I do everything possible.’

Mr Tamburrini has only snatches of memories of that first year in hospital but he remembers Prof Altman.

‘Prof Altman was a human being of a different level, something you don’t find in regular people,’ he says, visibly moved. ‘He was exceptional – and he was incredibly modest.

‘He operated on thousands of children; he was a pioneer in lots of fields of paediatric surgery. Not long after my surgery, he undertook a separation of Siamese twins, one of those first-in-the-world kind of things. He never had any personal relationship with patients outside of hospital – but for some reason he made an exception for me.’

When Alessandro went to New York, his surgeon would welcome him at his home, take him out to the famous Peter Luger Steak House, give him Yankees hats and socks. He even visited Alessandro’s village in central Italy, where he was welcomed as a hero.

Prof Altman, who had a passion for training, was proud of Alessandro’s career choices, though prescriptive about him pursuing a ‘meaningful’ type of surgery.

‘Going into surgery was not even a choice,’ says Mr Tamburrini. ‘I couldn’t have a different working environment than a hospital.’

Prof Altman, who developed Parkinson’s disease after becoming vice chief of medical affairs at Columbia, died in 2011 when Alessandro was still in medical school in Rome. Though Alessandro was never taught by the professor, he inherited his lab coats and name badge. His death left a ‘great void’.

Mr Tamburrini learnt years after his surgery that Prof Altman had never charged the family for his work.

Humble surgeons

Paying tribute to Prof Altman publicly has meant opening up about his own medical history, something Mr Tamburrini has tended to avoid.

It is only this year that he chose to do both, through the unlikely medium of the journal Pediatric Radiology.

In a letter to the editors, he refers to a ‘case series’ in the same journal in 1992, written by Prof Altman and others, about the importance of magnetic resonance imaging. The piece included scan images showing how a large tumour in a young child had originally been mistaken for his bladder. This ‘Case 2’ was Mr Tamburrini himself.

‘I didn’t know I wanted to write that paper but I thought I had left it long enough,’ he says now.

Part of this reluctance to talk about his experiences was never wanting people to define him or provide ‘any excuse for failures’, as he puts it. ‘I don’t want this to affect how people treat me. I never wanted sympathy.’

Nevertheless, his long experience as a patient has made him think carefully about the type of doctor he wants to be and how he can emulate Prof Altman and others he admired.

He speaks affectionately too of his Neapolitan oncologist Ludovico Guarini and his orthopaedic surgeon, Prof David Roye, whose odd socks disconcerted Alessandro’s mother so completely at first.

‘The true, best surgeons are humble people, not those who shout or affirm their charisma. Being confident is a positive thing in this job, and you need authority too, but Prof Altman, Prof Roye, they treated people nicely. I saw them taking extra time for everyone, not just for me, so this is what I tried to absorb.’

In signing off his tribute to Prof Altman in Pediatric Radiology, Mr Tamburrini writes: ‘I feel like I am carrying on his legacy in every surgical challenge that I accept.’

Mr Tamburrini came to the UK in 2015 to complete his training. Since then, he has established a reputation as a surgeon who, like Prof Altman, takes on complex cases others decline. His early health struggles, he says, have made him a ‘very ambitious, committed challenges-lover’.

Prof Altman was a human being of a different level, something you don't find in regular people

Alessandro Tamburrini

His appearance last year in BBC TV’s Surgeons: At the edge of life, where he was filmed removing a large, invasive tumour and the upper lobe of a patient’s lung, led to a deluge of emails from people wanting him to take on their cases too.

He has taken on more paediatric cases recently and believes Prof Altman would approve. He mentions a case referred to him from Great Ormond Street deemed ‘very dangerous’ – a young girl dying from an invasive lung aspergilloma, which complicated her treatment for lymphoma. ‘It still has to be done, I can do it,’ had been his reply. And he did, successfully.

‘I have to say that not everything goes well,’ he admits. ‘To do this job, you have to shield yourself a little from the emotional part, otherwise it’s impossible. I take things on as if they were tasks. And I am generally very blunt, which I realise is sometimes perceived negatively.

‘But I think I genuinely care for everyone that comes into my pathway. I take on board all sort of difficult, borderline, nearly impossible, high-risk cases. This is what I do, and I love it. There’s nothing else I will do.’

'Survival awareness'

Inevitably, perhaps, there’s a certain drivenness about him, which he recognises.

Mr Tamburrini is on sabbatical at Leuven Hospital in Belgium, for further training including lung transplants and complex oesophageal surgery.

Last year, he nearly missed his own wedding. He had scheduled his flight to Italy close to the big day, to fit in an operation, but global IT outages meant his flight was cancelled.

He was still on the phone to patients the day he married Sara. ‘Who speaks to patients the day of their wedding?’ he asks, perhaps of himself.

It was also the 33rd anniversary of his first major operation as a child, under Prof Altman.

‘I’m not really the best person to talk about work-life balance. For me, it’s very subjective. If you do a job you love, where is the balance?

‘The commitment to my job is at the expense of my personal and social life. I’m always looking for other challenges. Nothing seems to be enough. My wife says I need to find peace.’

Quite what drives Mr Tamburrini he finds hard to pin down. But he clearly feels he has a debt to pay.

‘No, I don’t have survivor’s guilt: I have survival awareness. Someone like me has the duty to try to make a difference because someone did it for me.’

![D3ca0010 Eba7 4297 8540 A3142c881a90[1]](/media/v5up1d1r/d3ca0010-eba7-4297-8540-a3142c881a90-1.jpg?width=600&height=600&format=webp&v=1dc6ea874591af0)